Academic advisor David Tate has ushered thousands of students through Purdue—but none quite so American as Karim Moshref, an Afghan refugee.

One fall morning in 1986, a serious young man with a square jaw and heavy brow—a man of extraordinary purpose—arrived without warning at the office of David Tate (M’70, MS EDU’80), director of Purdue’s highly competitive Medical Laboratory Sciences program.

“There was this intensity that just oozed from every pore,” Tate says.

To make sure his advisees felt comfortable, Tate rarely used the overhead lights; instead, he installed a series of table lamps and often tuned his radio to the campus NPR station, which aired classical music throughout the day. He kept a clean desk and lined the walls with books and pictures of his family, aiming for a vibe he calls “your uncle’s cabin in the woods.”

The young man—never dropping his gaze—introduced himself as Karim Moshref (HHS’89). He said that he and his family were from Afghanistan—from Kabul, the capital city—and that he was here now, in Tate’s office, to enroll in the premed program at Purdue. He wanted to become a doctor, he said. Again. Tate flipped through Moshref’s file as they spoke, astonished by what he had already accomplished—a seven-year medical degree from Kabul Medical University, four years of practice with various groups in Pakistan—and dreading the conversation soon to follow. Despite his credentials, Moshref’s CV was virtually useless in the United States. Nothing would transfer.

“When I looked at that, it broke my heart,” Tate says.

But Moshref himself was unflappable, rigid in his seat, deliberate in his every word. He wasn’t fishing for pity or favors. He was simply ready to move forward. To start again. Tate would often ease students into the program, sign them up for a few classes and test their appetite for the rigors of the program.

“But with Karim, I didn’t even try to talk him out of it,” he says. “We sat down and plotted it out, and I’ll tell you, it makes me nauseous—I felt totally helpless. I just felt absolutely, totally helpless.”

And Tate didn’t know the half of it.

The son of a retired colonel in the Afghan army and the youngest of five children, Moshref grew up near the city of Sheberghan, roughly 600 kilometers north of Kabul, near what was then the border of the Soviet Union. He graduated at the top of his high school class, and after completing the national university entrance exam— called the Kankor—he was one of 180 students across the country and the first in 10 years from the Jowzjan province to score high enough to enroll at Kabul Medical University.

Moshref had just begun his third year of medical school when Afghanistan’s Communist Party—backed by the Soviet Union—initiated a coup d’état, assassinating President Mohammed Daoud Khan and his family and installing a new regime. Roughly a year later, on Christmas Eve 1979, the Red Army invaded, deploying nearly 200,000 soldiers across Afghanistan and more than 80,000 into Kabul alone. Under the new leadership, academic standards at the university actually relaxed, Moshref says. They graded on a curve and allowed students to retake exams, rather than the pass-fail system previously in place, which typically culled the graduating class by roughly a third.

“The problem was our inside instincts were so anti-Russian, we never could settle with the government rules,” he says. “We thought anything they said was wrong, which was obviously immature, but I was an immature age at that time.”

The Soviets set up checkpoints all over the city and initiated an 11 p.m. curfew. Soon after the soldiers arrived, students in his dorm began to quietly disappear—friends and relatives, too. Pulled away for questioning by Communist Party authorities, most students never returned. By the time Moshref finished his degree, the Communists and their Soviet allies had killed nearly a third of those in his dorm—roughly 1,000 students. And by all rights, he says, he should have been one of them.

“I didn’t care about anything. I said whatever came to my mouth. Looking back, that was the most stupid thing I could do, but at that age, I couldn’t see the danger clearly.”

His own roommate, a member of the Communist Party, eventually reported him for mocking Soviet culture—growing up on the border, Moshref had plenty of material to draw from— and soon, like all those who simply never returned after curfew, he found himself answering questions before a high-ranking general, certain he was the next to go. Instead, for reasons he’s never understood, the general handed him a pen and paper. If Moshref admitted to his guilt, he said, he could walk free.

“I already got the point, but then he pulled open a drawer, and you could see a thousand envelopes in it. He said, ‘Each envelope is a person. Each person is one of your roommates, classmates, whatever. I send them away and they never come back again.’”

By the time Moshref earned his medical degree in February 1982, there was little question he would leave Afghanistan. But with Soviet checkpoints all over the city and a new wife alongside him, bucking Kabul—let alone the country itself—was hardly a straightforward task. Moshref hired a smuggler, who followed a well-known escape route to Pakistan. When they arrived at the Spīn Ghar mountain range, a snowstorm blocked the pass, forcing them to reroute and rendering their guide unable to help. What should have taken three hours ultimately took 11 days and numerous modes of transportation, all of which were “very unpleasant.”

“And that was our honeymoon, by the way,” Moshref says. “Even now, my wife jokes that our honeymoon was in the back of a tractor.”

Fresh out of medical school, Moshref immediately set to work in the city of Peshawar, helping care for the more than 400,000 other refugees who had fled Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion. He worked first for the Afghan freedom fighters—known as the mujahedeen and backed by the United States—and later for the International Rescue Committee, a nongovernmental humanitarian relief organization. Though he sometimes conferred with the Arab doctors, he was essentially on his own. Sink or swim.

“Learning as a student is very different from practicing as a physician,” he says. “The people look at you with a different hope. You’re 25 years old, and you’re practicing like a doctor, and that’s it. The field is wide open. Anything you want to do, you do it.”

After a year on the front lines of the refugee crisis, Moshref’s wife gave birth to their first child, a daughter. One and a half years later, she gave birth to their second, a son. “But down deep in my heart,” he says, “the problem was not only money; the problem was the freedom, the education, the learning.” Despite living “the fanciest life you can live in Pakistan,” he never had any intention of settling in, especially now that he was a father.

Moshref first applied for asylum in France, where his medical license would be honored, but without a sponsor, his application was denied. Germany was also on his list, though it would have required another covert smuggling operation, which he’d grown weary of. But the United States, where his sister and brother-in-law already resided, fit the bill, and he could emigrate legally, free from the yoke of secrecy. After four years in Pakistan, the Moshrefs finally landed in West Lafayette, where his sister was already a student at Purdue and his brother-in-law a professor.

Soon after they arrived, Moshref met with the director of the Indiana University School of Medicine, who’d previously taught internal medicine in Afghanistan. Still identifying as a doctor, Moshref wanted to know if he should pursue his board certification, uncertain of the American logistics. The professor told him frankly: “We don’t need you.” “He was friendly. This was not an insult. He said, ‘You have to prove yourself different,’ and one of the ways that I proved myself different was that I went back to Purdue like a regular student.”

And thus, Moshref found himself one morning sitting before the director of the Medical Laboratory Sciences program, classical music softly spilling from an unseen radio, awaiting the blueprints for his future. The file Tate held in his hands didn’t mention Moshref’s childhood on the Soviet border, the Communist Party, or the 80,000 soldiers who upended his life, his covert honeymoon, or all those envelopes—so many envelopes—filed back-to-back-to-back in the general’s desk. The file didn’t mention his kids or the new life he would build for his family. No, Tate didn’t know the half of it. But he could read the intent in the doctor’s shoulders, the drive in his voice, the determination in his posture. And as the two of them mapped out the road ahead, Moshref quietly nodding while his former accomplishments fell by the wayside, Tate thought, “I’m gonna do everything I can to help.”

Compared to what Moshref had already faced, his assistance felt like a minor contribution. But Moshref saw it differently.

“The process to enter the University, to get credit for whatever you have done—these are not simple things,” he says. “He was very helpful to me. But he was not just my mentor. He was not just the director of Medical Laboratory Sciences. That was not the case. He was a good friend and is a wonderful person.”

After three years as a medical technology student at Purdue, Moshref began his clinical year at Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis. “It’s harder to get into than med school,” Tate says, “because there are so few positions” in the program’s articulated hospitals. He then completed medical school all over again, this time at the Indiana University School of Medicine, before continuing on to his family practice residency in Fort Wayne. Finally, in May 1995, Dr. Karim Moshref caught up to himself, launching a solo practice in Fort Wayne.

“I knew what the fight was, and I was ready for it, so the fight itself didn’t hurt me,” he says. “But there is a hole for a few years in between my lives, and I don’t know where the hole went. It caused me to go from being a doctor to a student, from a student to a worker, from a worker to a resident, and then a doctor again. So it’s a little bit of an enriched degree, but I could perform the same way with one degree without having four degrees.”

Eventually Tate and Moshref—caught up in life and work—lost touch. Tate continued growing the Medical Laboratory Sciences program. Moshref continued building his family practice. But as the years passed, Tate often caught himself reliving one memory over and over again—a memory brimming with gratitude and spice. A reminder of “what people are willing to gamble,” Tate says, and “the responsibility given to those who shepherd them along the way.”

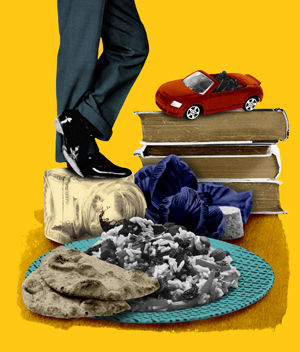

After he graduated from Purdue, Moshref invited Tate and his wife to dinner at his home, a small but immaculate apartment on the outskirts of the city. When they arrived, the air was thick with cardamom and turmeric, cumin and saffron, and their dining room table was a smorgasbord of homemade Afghan cuisine: meats and breads, fruits and vegetables, and a special dish called Kabuli pulao with ingredients near impossible to find in West Lafayette.

“There was food on the table that I’ve never had since then, and we’ve traveled all over,” Tate says. “I’ve never had food like that in my life. If somebody said, ‘David, you get a choice on your last meal,’ I’d call Karim and say, ‘Hey, ask your wife ….’ It was just that good.”

Before they left, Tate gifted Moshref’s son a small Matchbox car—one of the only toys he’d ever received and one he’d cherish, unbeknownst to Tate, for years to come. On the way home, Tate and his wife sat in disbelief, truly astonished by the meal, by all the work Moshref’s wife, Rahela, had done to prepare it, and by the sheer earnestness with which the whole family expressed their appreciation. But Moshref thought it was the least he and his family could do.

“When you go through a difficult time, you want to appreciate the people who are there for you,” he says. “I’m privileged to have friends like him.”

Nearly 20 years later, after the Medical Laboratory Sciences program had moved into a new wing of the civil engineering building, another young man with a square jaw and heavy brow—a man of few words—visited Tate’s office. His secretary said the young man, Nawid Moshref (HHS’11), was hoping to transfer into the premed program. At the end of their meeting, Tate glanced at the young man’s folder again, taking special note of the last name.

“You know, years ago, I had a gentleman come in from Kabul, Afghanistan.” He told Nawid about the many sacrifices of Karim Moshref. About his education in Afghanistan and his wife and his kids. Speaking Farsi in their home. That great meal he would never forget. And the tiny Matchbox car he gifted their son before they left.

Nawid waited patiently for Tate to finish his story, leaned gently forward, and said, “That was me.”

“I don’t even know if I said anything,” Tate says. “I was stunned.”

And he didn’t know the half of it.

At just 17 years old, Nawid enlisted with the National Guard. A year later, after graduating from high school in Fort Wayne, he completed his basic training in Fort Benning, Georgia, and later enrolled at Purdue as an engineering major. But the studies didn’t stick, and he soon returned to the military, enlisting full time in the U.S. Army.

“It was an opportunity to serve a country,” he says. “Especially one that kind of adopted us after Germany and France said no.”

Though he told his parents he’d be doing something medical related, he instead dove straight into the airborne infantry, later volunteering for tryouts with the 101st Pathfinder Company at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He made the cut and was soon promoted from junior enlisted to non-commissioned officer.

“I was kind of hesitant, because I’d never really led troops in combat,” he says. But like his father suddenly treating patients fresh out of med school, Nawid—ready or not—quickly found himself leading a long-range reconnaissance unit in Iraq. They worked almost exclusively under the cover of night, when they had the greatest advantage, but they found themselves one afternoon outside the city of Balad, approaching something they couldn’t identify in the road ahead. It wasn’t until his partner motioned for him to stop that he saw the wiring beneath him, but it was already too late.

“We were far enough away from the initial blast that the concussion didn’t tear off limbs or anything like that,” he says. “But the blast threw me across the desert. I lost consciousness, and then once I regained it a few seconds later, I realized I was in the kill zone.”

Enemy fire erupted from a berm off the road. Heavily concussed, Nawid ran toward the action. Eventually they called the medivac to whisk him away and tend to the shrapnel in his face—but not before quelling the initial ambush. Four-star general Peter Schoomaker, the 35th chief of staff of the U.S. Army, would later award Nawid a Purple Heart for his sacrifice.

“I don’t think I really went above and beyond— maybe just the bare minimum,” he says. “When you see other people that gave a lot more, and some that gave everything, it’s hard for me to say, ‘Oh, yeah, I’m in the same boat as them.’”

After 13 months in Iraq and a final summer at Fort Benning training soldiers in hand-to-hand combat and medium-range missile systems, Nawid returned to Purdue, this time as a premed student. Tate was shocked enough to find Karim Moshref’s son sitting where his father had so many years before, but when he spotted Nawid at a Veterans Day ceremony during his senior year, his uniform highly decorated, Tate could hardly contain his admiration.

“Here’s Nawid in his dress blues, all these ribbons—it was hard not to get choked up,” he says. “I’m looking at this kid, and I’m thinking, ‘That is the American story right there. That is exactly what the framers of our Constitution had in mind.’”

Nawid later earned his physician assistant degree at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He now lives near Baltimore, where he works in cardiac critical care and in the biocontainment unit at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

“It warms my heart to think that I had this little part to play in their lives,” Tate says. “I will always think of them when I hear people say, ‘Oh, I’ve had a tough year,’ or this or that.”

On those occasions, Tate leans forward in his seat, pausing to let the story settle in. “Let me tell you what sacrifice is….”