Mother’s poignant words led Frank Brown to the Pinnacle

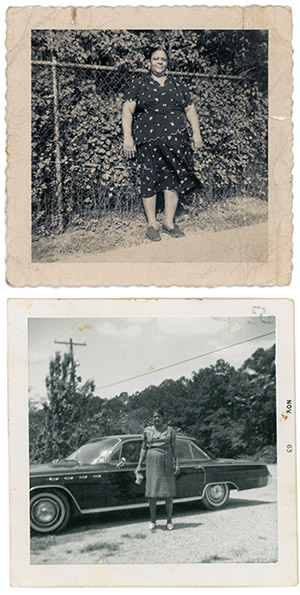

Frank Brown’s mother was illiterate. As an African American woman who lived in the first half of the 20th century, Amanda Brown was not afforded an education. “She couldn’t read, but I didn’t know this,” Brown (PhD S’69) says. “She critiqued and praised my schoolwork. She knew the difference between an A and a B and the difference between 100 and less than 100, so she wasn’t stupid by any choice; she was uneducated. She mentored me.”

“She couldn’t read, but I didn’t know this. She wasn’t stupid by any choice; she was uneducated. She mentored me.”

—Frank Brown regarding his mother

Amanda Brown died of a stroke at age 50 when Brown was 11. She lives on in her son’s scholarship and deeds. During his 31-year career at Eli Lilly and Company and service as an adjunct professor in Purdue’s departments of Chemistry and Industrial and Physical Pharmacy, Brown has lived as a mentor.

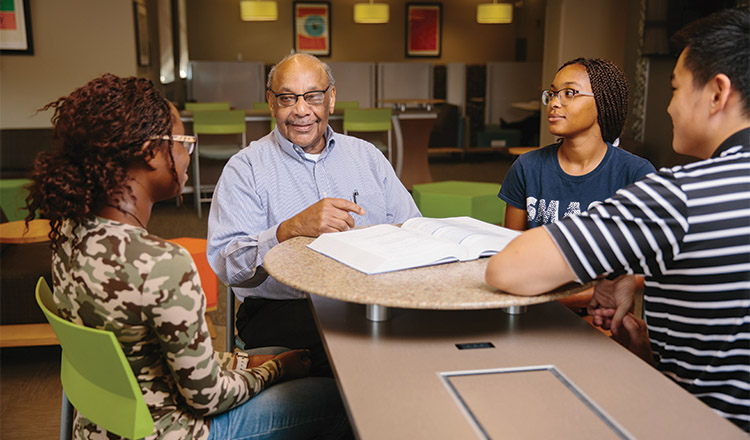

Recently, Brown gave to establish the Frank Brown Distinguished Professor of Chemistry. In May, Brown was presented Purdue’s Distinguished Pinnacle Award by President Mitch Daniels at a reception in Leighty Commons, the south entrance of Wetherill Laboratory transformed in 2014 into a student meeting space with a chemistry-themed décor — Brown’s brainchild.

Brown was born in 1942 in a Detroit ghetto. His parents moved there from Mississippi during the Great Migration of African Americans. His father worked at Ford Motor Company as a sweeper, cleaning up oil, making $9 a week.

Brown moved to Louisiana when he was 10. It was immediate culture shock. “The first day off the train — it was hot down there — I walked over to a drinking fountain and took a drink,” Brown says. “A man said, ‘Get that boy off of there. Doesn’t he know any better?’ to my father.”

Brown’s father was also illiterate. When Brown turned 13 and could read, write, and count money, his father wanted him to quit school and go to work. “The bottom line was, he didn’t allow me to go to high school, so I left home,” Brown says. “I walked to my grandmother’s house 16 miles away.”

Brown remembered his late mother’s words: “An education is the only thing that a man cannot take away from you.”

After high school, Brown earned a BS in chemistry from Southern University and A&M College, the school for black students. He discovered Purdue for his PhD through a friend, an engineering alumnus working for Exxon, who gave him a ride to class. “He mentored me. I didn’t know what mentoring was at that time, but he saw I had calculus books,” Brown says. “He suggested that I get out of the South and that I look at Big Ten schools.”

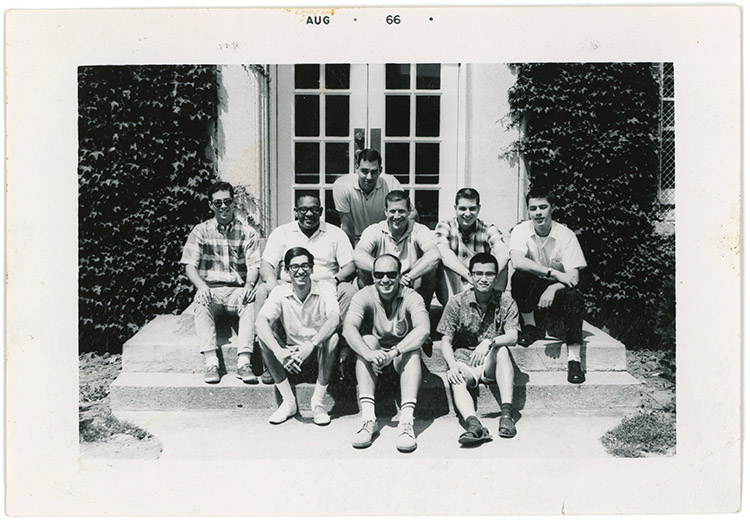

Brown was accepted to nine of the Big Ten schools. Purdue offered him the most money as a teaching assistant. The first day Brown walked into the all-white classroom in 1964 the students looked stunned. Yet, they learned quickly that Brown is an excellent teacher. “I prided myself on having the highest-scoring students. I made sure they knew how to work the problems, which was key to passing the course.”

Brown was in Henry Feuer’s research group. Feuer and his wife, Paula (PhD S’51), who taught physics, became advocates. Henry Feuer was a Holocaust survivor.

Brown did not realize that Feuer, too, was a minority. “My lab partner, who was Jewish told me, ‘Being Jewish is not exactly like being white,’” Brown says. “I couldn’t understand that. I didn’t know that Jewish people existed outside of the Bible. Nobody ever told me that. Furthermore, nobody had ever told me that the Holocaust had happened.”

When Brown told his lab partner that he had never heard of the Holocaust, the man wept. “I didn’t know about Hitler. My lab partner took me to the Sweet Shop and told me more. I couldn’t believe it. By the time we left, we were both crying. I was angry that the history teachers in Louisiana didn’t teach this. I wondered what else they did not teach.”

After receiving 15 job offers, Brown decided on Eli Lilly in Indianapolis because Feuer said, “In all my dreams, I never thought I would have a student good enough to get a job offer at Lilly.”

At Lilly, Brown conducted research on the antibiotic Keflex and mentored technicians. “The first person I mentored was a middle-aged woman whom I taught freshman and organic chemistry,” Brown says. “She was promoted after applying the knowledge I taught her.”

Brown received two President’s Awards from Lilly. During this time, Brown was awarded Purdue’s College of Science Distinguished Alumni Award. After he retired in 2000, Brown became director of the Purdue pharmaceutical sciences program. He volunteered to tutor minority students in organic chemistry. “The one I remember the most was a white girl who came to my office. She said, ‘I’m here because my roommate is a black female. You’re mentoring her. I’m having even more trouble than she’s having. Is there any way you can make an exception and mentor me?’” Brown said, “Sure. All university programs are open to all students.”

Four years later at commencement, the young woman received her doctorate of pharmacy degree and introduced Brown to her parents. She said, “If it were not for this man, I would not have graduated.”

“She probably means the most to me because I only tutored her on three occasions,” Brown says.

Brown was the impetus behind the Donor Wall in the Herbert C. Brown Chemistry Building, created to recognize donors and inspire others to give. “I’m very proud of that, but I did that anonymously. You can talk about it now. I don’t like to toot my own horn. I’m a values-oriented person. I like to do the right thing for the right reason without bringing attention to myself.”

His mother’s prophetic words about a black man’s education pulse gently under Brown’s actions. He dedicated his doctoral thesis to his mother. “She’s with me 24/7. Always will be.”